In our own era, recent immigrants and refugees sometimes endure unfavorable comparisons to earlier immigrants, including those who migrated from southeastern Europe to Soulard in the early 1900s. Back then, it is sometimes claimed, immigrants embraced their new homes while eagerly seeking to become English-speaking Americans. Now, so the story goes, the melting pot no longer works, and immigrants’ retention of separate identities poses a threat to American culture.

But this purported contrast between then and now founders upon the evidence. Consider, for example, the experience of librarians at the Soulard branch library in south St. Louis, who regarded Americanization of the neighborhood’s immigrants a key part of their mission, especially through the teaching of English.

The Soulard branch library was opened in 1909 in large measure to serve and thereby Americanize the neighborhoods’ foreign population–a goal that met with limited success, especially among adult immigrants. Since about 1900, Soulard’s new arrivals from southeastern Europe, who numbered in the tens of thousands, had adapted the languages and customs of their homelands to their new industrial environment by forming new families and communities that rested upon shared ethnic identities. Their sheer numbers made it possible for them to retain their ways of speaking and relating, not only in their homes but also in their churches, workplaces, and saloons. After the U.S. entered the war, official and popular hostility to “enemy aliens,” including Germans and Hungarians from the Banat, deepened immigrants’ resistance to being changed. Official restrictions on “enemy aliens” legitimized xenophobia; immigrants, in turn, became increasingly suspicious of efforts to Americanize them.

A 1917 account by St. Louis librarian Margery Quigley sheds light on the frustration of Soulard’s patriotic librarians, especially Josephine Gratiaa, head of the Soulard branch library. It also offers tantalizing glimpses of the contempt for Americanization felt by Soulard’s immigrants, who remained strongly connected to their “old world” families and identities and who knew first-hand the value of their language and customs to their survival and self respect. Noted Quigley with apparent bemusement:

“Several classes have been opened at different branches to teach these women English, but they have evaporated in a few weeks. The women are sensitive, and suspicious as well, especially since the war began. They are afraid that they will be arrested as spies. Miss Gratiaa, of the Soulard Branch, reports that no foreign adult will consider having his picture taken in any position in the library, even by a friendly and plausible library assistant, for he is thoroughly convinced that it is some sort of war-trap. Even before the war, the women preferred the safety of home to the invasions of an unknown social world. One group of Hungarian women was dragooned by a social worker and a steamship agent’s wife into organizing to study English. The women came to the library once and stared for an evening at the charmeuse dress and fresh complexion of the debutante who was their teacher. The next week they went on strike without warning and allowed the instructor and her protector to twirl their thumbs until the library’s closing time.”

Gratiaa shared Quigley’s frustration. In 1918, she speculated that “there is certainly an insidious propaganda working among the foreign born, which is preventing, as far as possible, their participation in any of the means of Americanization.” She further noted that “many English classes among foreigners at near-by factories have had to be abandoned for non-attendance.”

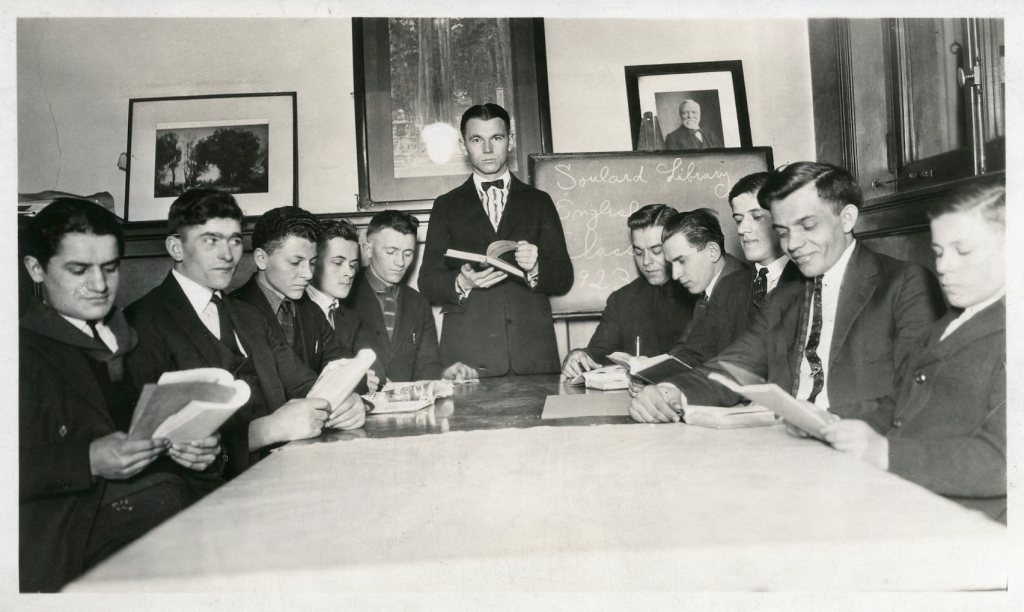

Even as they encountered stiff resistance, St. Louis’s proponents of Americanization went to great lengths to document their efforts, of which they were clearly very proud. Dozens of surviving photographs from the early twentieth century–many of them carefully posed–depict immigrants studying English in classes sponsored by the YMCA, including classes taught at the Soulard branch library. In 1919, Gratiaa published an monograph titled Making Americans: How the Library Helps, in which she extolled “the importance of the Library in any scheme of Americanization.” Central was the library’s role in teaching English to immigrants–either indirectly, by providing books in English, or directly, by offering English classes. Wrote Gratiaa, “the war revealed the necessity of teaching English to all our alien population. This is imperative not only because of temporal advantages such as the increase of industrial efficiency and the prevention of accidents, but also because until the foreigners learn English, they can never completely understand us or become a real part of American life.” To her credit, Gratiaa cautioned that “no attempt must be made to prevent the use of other languages, because we believe that the native heritage of the foreigner must not be lost.” But her emphasis was clear: “English is the language of this country, and no immigrant is ever completely Americanized until he can use it.”

English, of course, would become the preferred language of immigrants’ children, who grew up hearing it and speaking it on the playgrounds, the schools, and the libraries, including the Soulard branch library. (In February, 1917, the St. Louis Star aptly described the children’s reading room of the Soulard Branch library as “the real melting pot of St. Louis . . . where children of all nationalities mingle and read books of their common foster parent, America.”) But among the parents–that is, among adult immigrants themselves–English was never as highly valued as the proponents of Americanization fervently wished. After all, why would any self-respecting immigrant choose to speak and write badly in a new language when the old one worked perfectly well–especially in the homes, the dance-halls, and the saloons? It was a hard lesson in rejection for the staff at the Soulard branch library who desperately wanted their adult clients to use English.