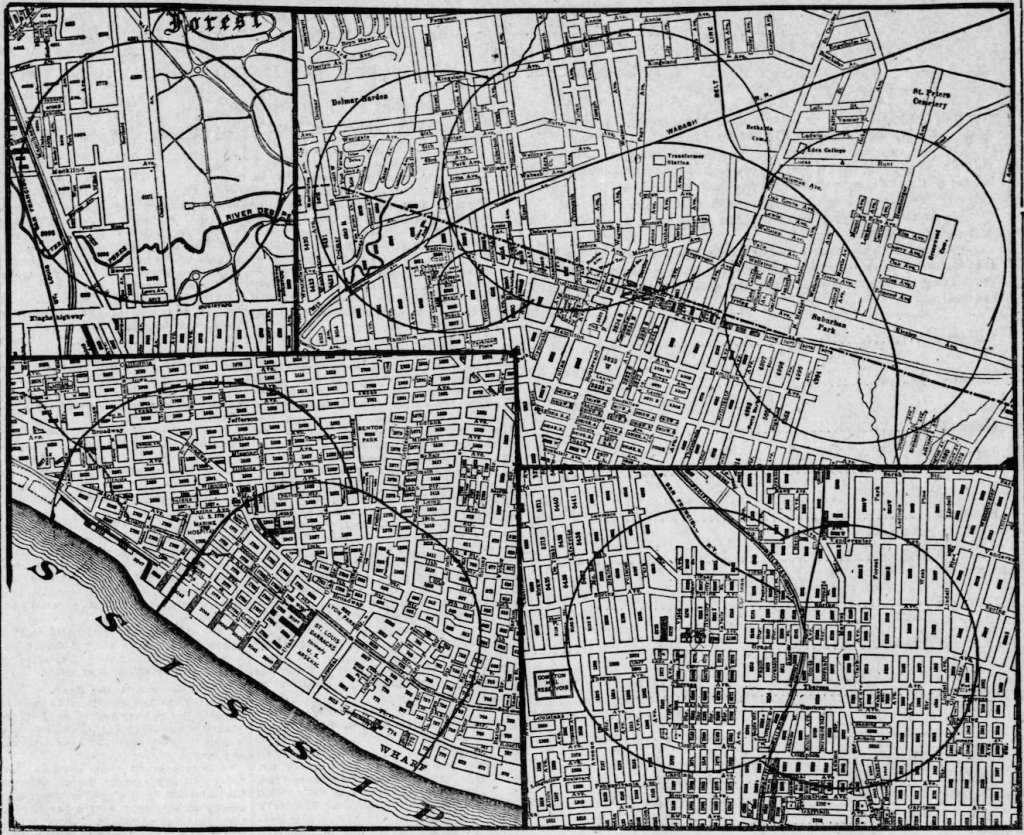

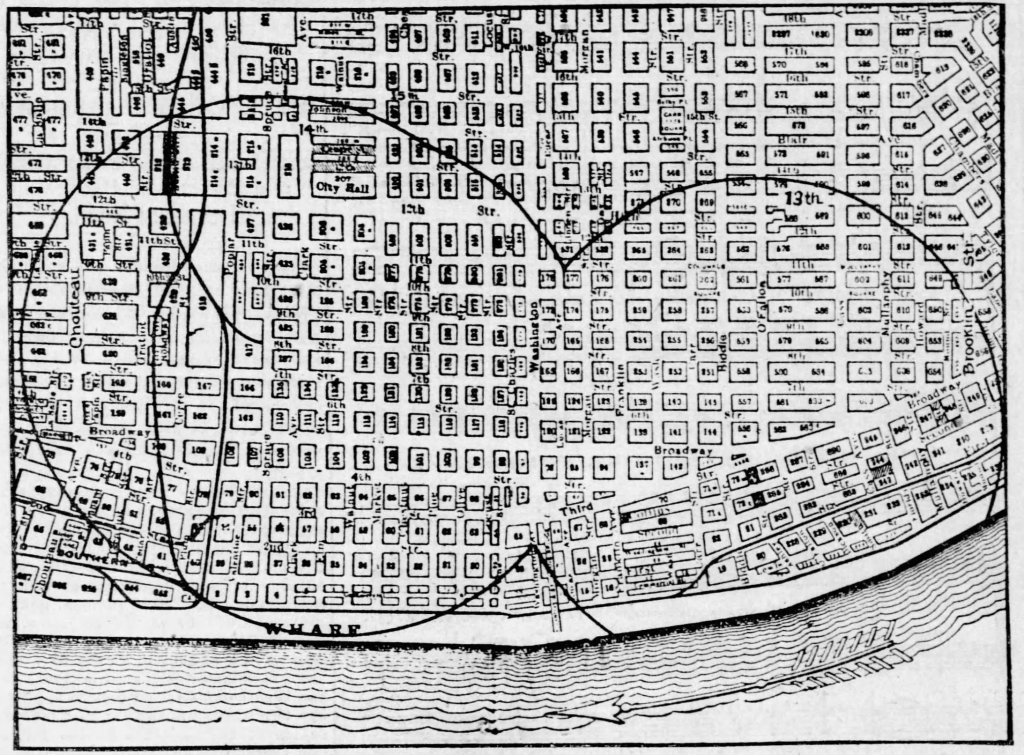

“In April, May, and June [1917], officials enacted a federal order barring unnaturalized Germans from coming within a half mile of any defense- related establishments. The political geography of St. Louis suddenly changed when, on April 20, the district attorney issued maps of St. Louis featuring mile- wide ‘barred zones’ that were off- limits to German nationals, on pain of immediate arrest. The measure effectively denied Germans entry not only to armories and arsenals but also ‘to the Free Bridge and Eads Bridge, to the McKinley Traction Company’s station on Twelfth Street, to the wholesale and part of the shopping district, to many theaters and motion picture shows, to the two German newspaper offices, the Amerika and the Westliche Post, and the City Hall and Municipal Courts Building.’ Soulard was sandwiched between an exclusion zone to the north that included the southern part of downtown and another to the south that included the Anheuser-Busch Brewery” (The Names of John Gergen, pp. 142-143).

I have searched every archive I can think of for the original maps showing the “barred zones,” with no success. But the Post-Dispatch published its own maps, and they reveal how much of St. Louis was off-limits to German nationals.

Alien exclusion zones were assiduously enforced among the thousands of German nationals living in St. Louis. Germans unlucky enough to find themselves living in one of the zones were forced to move. Those who worked in one of the zones were obliged to apply to the U. S. Marshall’s office for permits to enter the zone; applicants’ names–hundreds of them–were often printed in the local papers. Citizens were encouraged to report to the police any incursions into the barred zone. Dozens of German nationals were arrested for living in or entering the barred zones, and some were interned for the duration of the war.

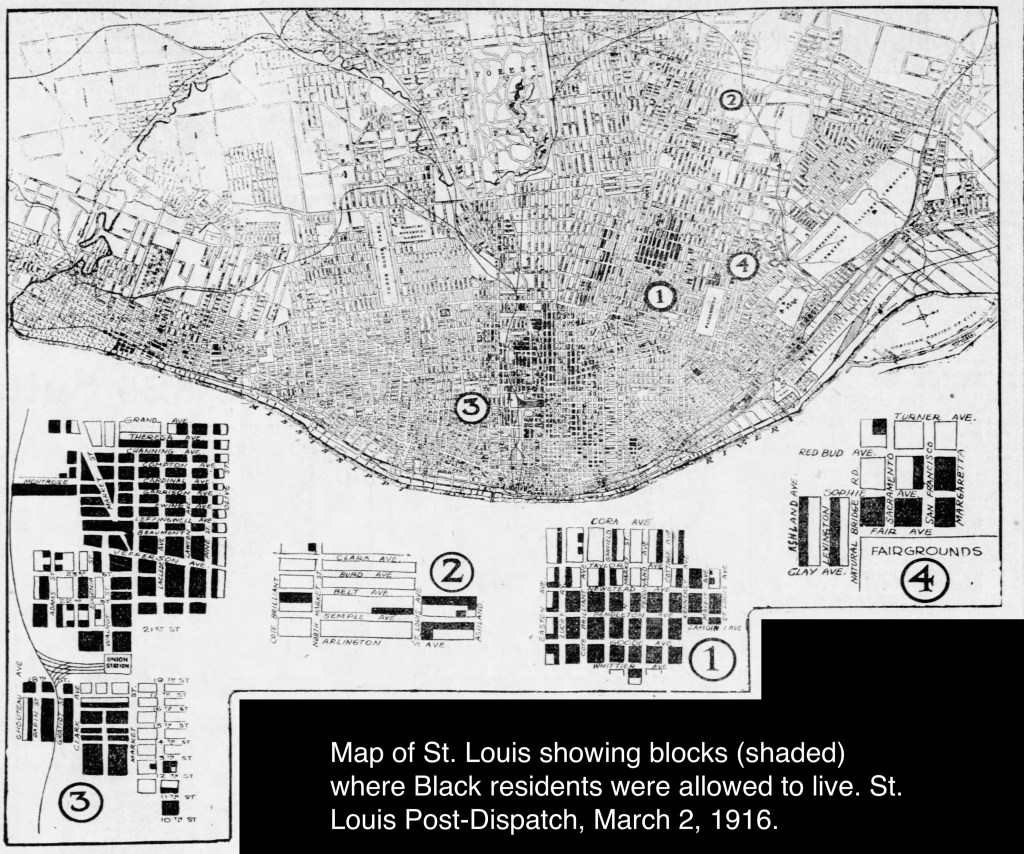

Nor was it the first time that the Post-Dispatch published a map showing where people were allowed to live:

“In 1916, with real- estate developers leading the charge, St. Louis residents overwhelmingly passed a referendum that ‘barred blacks from purchasing a house or residing on blocks that were more than 75% white and vice versa.’ In March 1916, the Post- Dispatch published a map showing the few blocks ‘where Negroes may hereafter take up residence.'”

In 1917, The supreme court would declare St. Louis’s segregation statute unconstitutional. But for white immigrants, who would come under increasing scrutiny during the war years, St. Louis’s racist and xenophobic maps would together provide a powerful impetus to secure working-class white privilege. The racist map, after all, warned immigrants as well as Blacks that there was a racial line that must not be crossed. And the alien exclusion zones of 1917 were a reminder of the government’s authority to sort, stigmatize, and restrict urban populations, right down to the level of houses, tenements, and streets. “[F]or working-class immigrants, who themselves had been systematically demeaned, racism was [to become] a fulcrum that enabled not only social and economic advancement but also— perversely—a heightened sense of self-respect” (The Names of John Gergen, p. 213).