The Names of John Gergen includes forty illustrations, several depicting John Gergen at various ages. I am grateful to John’s cousin and goddaughter, the late Anna Cattaneo, for providing six of the photographs that are included in the book.

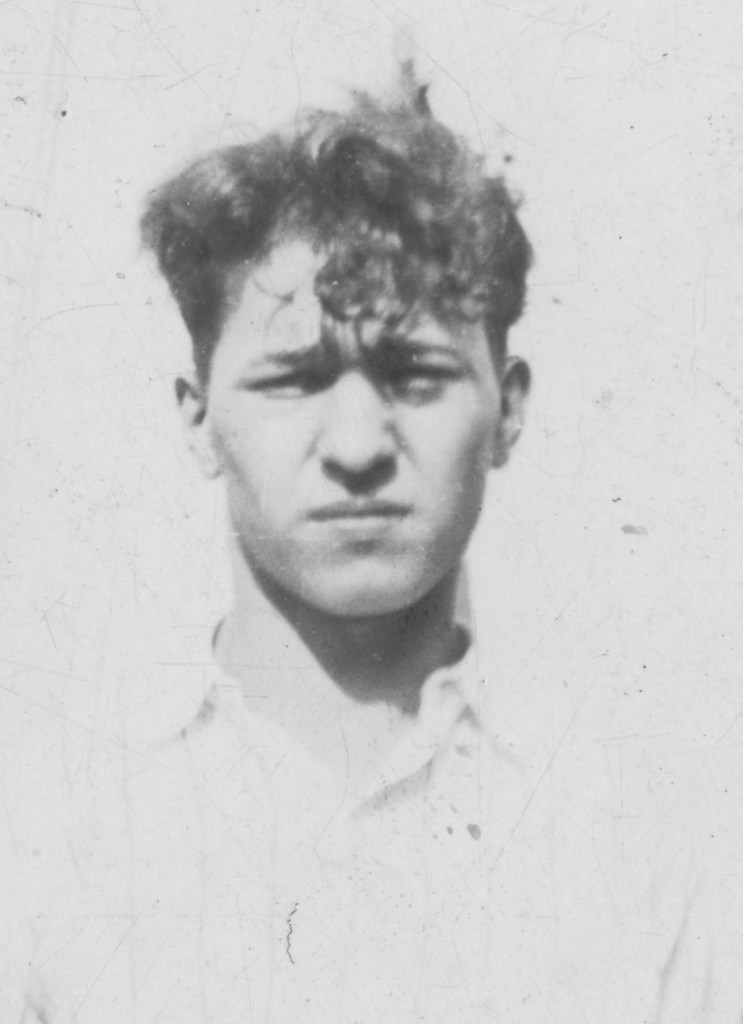

The snapshot below is not in the book. It was probably taken two or three years before John’s death in 1935, after his disappointments in life had become apparent and possibly after he had been diagnosed with tuberculosis. The expression on John’s face is haunting. His look is penetrating, as if he could see the future, including his early death.

Another photograph of John resonates even more strongly with what I have learned about his troubled identity. It depicts him standing in the backyard of his aunt and uncle’s house in south St. Louis. His foster parents stand beside him, and two of his cousins–both young girls–stand in front. John’s story is inscribed in his appearance: his awkward height, his sad and perplexed expression, and the thinness that would become gauntness when the tuberculosis grew worse. His face is blurry, as if to suggest his own vexed identity, which never really resolved into individuality but was instead parceled out among the families, nations, and institutions that structured his short life.

The photographs are small, about the size of a playing card. That we still have them some ninety years after they were taken is remarkable. Anna Cattaneo passed them on to me in 2005, when she was 78. By then, John Gergen, who had no descendants, was virtually forgotten. The fate of these photographs could easily have been the same as the faded snapshots and studio portraits that turn up at flea markets and antique malls–anonymous people who stare out at us from oblivion, unable to tell us who they are. And far more fragile than the photographs are the memories that give them meaning. When Anna died in 2015, we may have lost the last person who had any recollection of John Gergen.

John was only one person. As I write in the book, he represents “those countless working-class immigrants who are more or less invisible in the historical record. They, too, had thoughts, feelings, abilities, shortcomings, and desires. About John Gergen, we know little enough. About the great majority of these immigrants, we know almost nothing.”