Excerpted from my book-in-progress, provisionally titled Aliens in the Crucible: St. Louis, Xenophobia, and a 1908 Immigrant Suicide. The book examines the political and cultural effects of turn-of-the-century xenophobia in a city that Walter Johnson calls “the crucible of American history.”

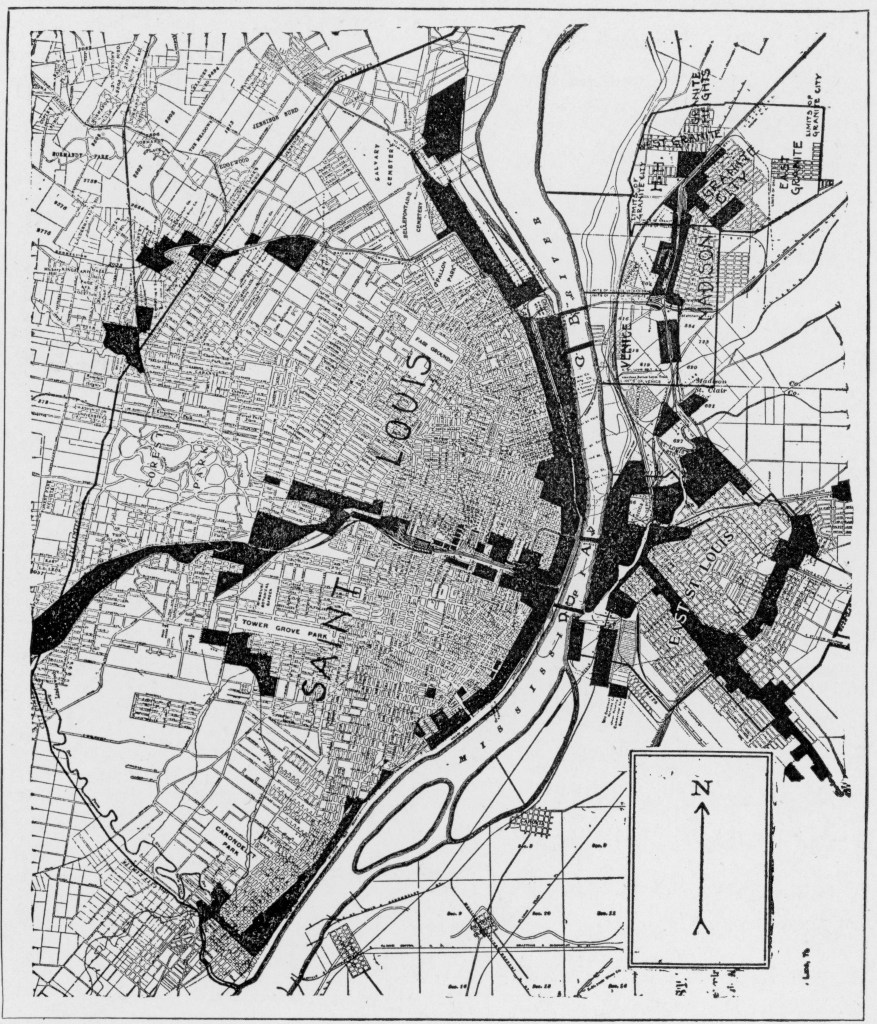

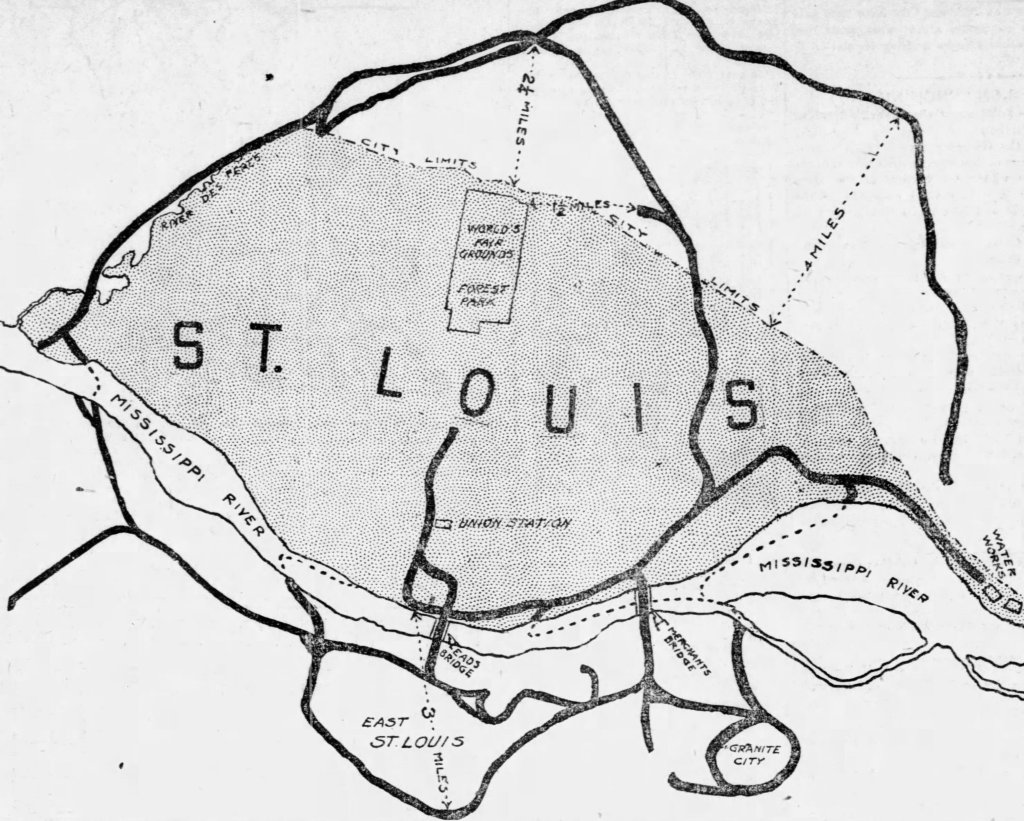

In addition to swelling the populations of St. Louis’s riverside industrial neighborhoods, immigrants increasingly populated the new industrial “satellite cities” on St. Louis’s east side. These areas, too, were part of a national trend. Wrote Peter Roberts in 1912, “hundreds of small communities have, in recent years, grown around industrial plants transferred from large cities, and with the plant the foreigners also moved. Around Pittsburgh, Buffalo, Chicago, St. Louis, etc., many such plants are found. They have been well called ‘satellite cities,’ for industrially they have to depend upon the parent city.”[i] St. Louis’s most important satellite cities, all across the river in Illinois, were East St. Louis, Venice, Madison, Granite City, and Wood River. There, on the “east side,” abundant water, readily available land, and cheap bituminous coal gave rise to foundries, factories, and an oil refinery. By 1907, these businesses employed thousands of laboring immigrants from Hungary, Russia, Bulgaria, Albania, and Greece. The industrial development and population growth in Granite City and Madison were especially spectacular. Reported the U.S. Immigration Commission in 1911,

“In 1892 the site of this community was an unbroken stretch of cornfields….During the two years 1894-1896 a large steel plant, including blast furnaces, rolling mills, and foundries, was established in the community. In 1901 another steel establishment of the same description began operations. Four years later a large company for the manufacture of corn products was located in the community. About the same time shops were erected for building wooden and steel [railroad] cars. These shops employed over 3,000 men. By the year 1900, as was to be expected, the demand for unskilled labor could no longer be supplied by English-speaking people alone.”[ii]

Between 1900 and 1910, the population of East St. Louis jumped from 29,655 to 58,547; of Madison, from 1979 to 5046; of Granite City, from 3122 to 9903.[iii] Romanians, Bulgarians and Hungarians were especially numerous, settling in a part of Granite City known as Hungary Hollow, sometimes called Hunky Hollow—“a forlorn neighborhood beyond the western bulwark of industries and railroads.”[iv]

Historians have sometimes treated St. Louis’s eastern satellite cities separately from St. Louis City, and with reason.[v]The Mississippi River was a formidable mental as well as physical barrier between the two parts of the metropolis. Federal censuses enumerated the two areas separately. More important, different state and city laws shaped labor and trade practices in Missouri and Illinois. The official industrial work week, for example, was fifty-four hours in Missouri but sixty in Illinois. St. Louis City had smoke regulations; the east side did not. Perhaps most important, surcharges imposed by St. Louis’s bridge “arbitrary” added twenty cents per ton to the cost of coal shipped west across the Mississippi River at St. Louis.[vi] Coal, much of it mined in southern Illinois, was therefore cheaper on the east bank of the Mississippi River than on the west bank. The price difference was a key factor motivating the founding and development of St. Louis’s eastern satellite cities.[vii]

But despite these barriers, the east side was an integral part of the St. Louis “industrial district,” economically and culturally. Most of the east side’s foreign-born residents had first immigrated to St. Louis before crossing the river again to reside in Illinois. Many other immigrants continued to live in St. Louis while working east of the river; factories even paid for workers living in St. louis to commute by train across the Eads Bridge and, three miles to the north, the Merchants Bridge. By 1912, 35% of Granite City’s 11,000 workers would reside in St. Louis.[viii] St. Louis’s Terminal Railroad, which handled all passenger and freight railroad traffic entering or leaving the metropolis, encircled St. Louis’s new industrial satellite cities, looping them into the metropolis and integrating them into the local economy. Environmentally, the industrial districts where immigrants lived were one big mess. Residents in St. Louis proper could all too easily see—and, when the wind blew west, smell— the smoke from the huge industrial chimneys across the river. St. Louisans, in turn, dumped plenty of smoke and odors on their neighbors to the east. Both sides poured industrial and human waste into the Mississippi River. For the factory owners and managers who lived in St. Louis’s newer residential subdivisions, pollution meant progress. For the industrial workers living in the lowlands on both sides of the river, it was another humiliating hazard.

[i] Peter Roberts, The New Immigration: A Study of the Life of Southeastern Europeans in America (New York: Macmillan Company, 1912), 116.

[ii] U.S. Senate, Immigrants in Industries (in Twenty-five Parts): Part 2, Iron and Steel Manufacturing, Volume 2, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1911), 43.

[iii] Graham Romeyn Taylor, Satellite Cities: A Study of Industrial Suburbs (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1915), 135 (originally published as Taylor, “St. Louis ‘East Side’ Suburb: How Industry is Jumping Across the Mississippi While Civic and Social Progress Follows Slowly, The Survey 24, no. 18 [February 1913]).

[iv] Taylor, Satellite Cities, 128.

[v] See, for example, David E. Cassens, “The Bulgarian Colony of Southwestern Illinois 1900-1920,” Illinois Historical Journal 84, no. 1 (Spring 1991), 15-24.

[vi] Taylor, Satellite Cities, 130-131.

[vii] Primm, Lion of the Valley, 398.

[viii] Taylor, Satellite Cities, 138.